From time to time I hear stories about Big Law offering Big Money to attract first year lawyers to sign away their souls in Toronto, or U.S. firms opening the vaults and waving around signing bonuses to lure Canadian legal newbies south of the border.

While throwing money at junior folks can be a good thing, I think that a warning is in order. Since no one else appears to be issuing one, yet again it falls to me to cut through the bullshit, state the obvious, and protect the new generation of lawyers.

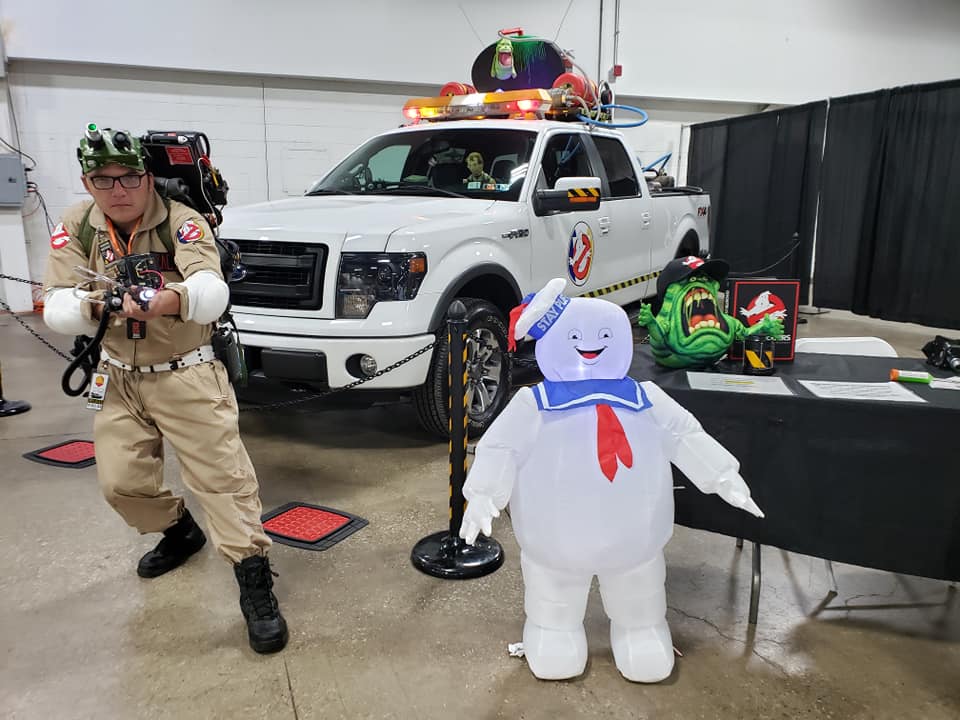

I will draw my inspiration from the love of my life, who, nurturing parent that she is, used to warn her young children about “Stranger Danger.” More specifically, she would say: “Don’t be stupid about it. Be sure that you see the candy BEFORE you get in the van.”

I will leave it to you intelligent young folks to search for meaning in my warning and being lawyers, Govern Yourselves Accordingly.